In this article, we’ll break down the basics of the Australian legal system and some of the ways it interacts with our healthcare and community care systems. You’ll learn more about the rule of law, the different types of law that affect us all – like criminal, family, and employment law – and how legal issues are commonly resolved in Australia.

Understanding how the Australian legal system works helps us understand our rights, make informed decisions, and navigate everyday situations in our personal and professional lives. If you’ve ever wondered how the legal system in Australia works or have encountered questions about it in the delivery of your work with clients or patients, use this guide as an introduction to get you started on your journey to learning more.

What is the ‘rule of law’?

The rule of law is a fundamental principle of the Australian legal system. In basic terms, it means that everyone – no matter who they are, where they live, or how much they earn – must follow the law. The rule of law helps protect our rights and keeps society functioning by making sure laws apply equally to everyone, including the people who make the law and our government. It gives people confidence in the legal system, which keeps everyone engaged and invested in working to uphold and improve it.

You might already be getting a sense of why understanding the legal system is so important: in a democracy, we all have a right and a responsibility to participate in holding the system up to its own standards. An effective legal system means that if someone violates your rights, you can expect the law to treat you fairly and provide a way to resolve the issue. When you know the rules are clear, fair, and enforced consistently, and you trust that justice will be done, you’re more likely to engage with the system – which makes the whole system stronger. Understanding the rule of law is key to understanding how the Australian legal system works and how it can be improved.

What are the basics of the legal system in Australia?

Now that we’ve covered the rule of law, let’s take a closer look at how the Australian legal system works. The basic structure is built on principles we inherited from the United Kingdom during colonisation, which is why there are similarities between our legal systems. At the heart of the system is the Australian Constitution. Think of the constitution like the foundation of the entire legal system. The Australian Constitution is not easy to alter – it can only be changed through a national referendum.

Beyond the constitution, Australia’s legal system works through laws made by the democratically elected legislature or Parliament – these are called statute laws. However, when a case arises that isn’t clearly covered by a written law, judges turn to common law, which is built on decisions made in previous cases. This idea of ‘precedent‘ – judges relying on earlier court rulings to guide their decisions – helps keep the common law consistent and stable. Even so, statute law will always override the common law where there is relevant legislation on a specific issue.

Australia’s government is a federation, so it has a hierarchical structure with three levels:

- The federal parliament makes laws that apply in the same way across all of Australia, like defence, telecommunication, immigration and welfare laws.

- Other laws are the responsibility of individual states and territories, so each state or territory parliament makes its own laws on a wide range of topics like mining, police, emergency services, roads and public transport. Some areas, like health and education, are shared between federal and state or territory governments – for example, the federal parliament makes laws about universities and state parliaments make laws about primary and secondary schools. If these two levels accidentally create laws that contradict each other, the federal law overrides the state law.

- And finally, local councils make by-laws about local matters like parking, rubbish collection and libraries. By-laws are delegated from the state government, which is allowed to overrule them.

As you can see, the hierarchy is carefully designed to avoid situations where it isn’t clear what the law is. Each level must make laws that are consistent with relevant legislation in the higher levels, and the buck stops at the constitution. You can find out more about the three levels of government from the Parliamentary Education Office.

The types of law

Laws in Australia can be grouped into two main categories: public law and private law.

These categories help us understand how the law applies in different situations, whether it’s between individuals or involves the government. Let’s take a closer look at what these types of law are and how they impact our daily lives.

Private law

Private law applies to relationships between individuals, and is concerned with issues like contracts, property rights and personal disputes. Employment law, family law, housing law and civil litigation are all categorised within private law.

Employment law

All employers have specific legal responsibilities to the people that work for them. For example, they must provide a safe place to work, and pay wages according to the minimum wage or the Award that covers their industry. Employment law sets out these responsibilities and regulates the relationship between employers and employees. This includes the Fair Work Act, Work Health and Safety Standards and anti-discrimination laws. Employment law also covers labour unions, negotiations and collective action by employees. Most laws relating to employment are federal, and apply wherever you live in Australia, but there are some laws that vary state by state.

If your workplace doesn’t seem to be following the law, you can talk to your union, your local workplace health and safety regulator, the Fair Work Ombudsman or a local community legal centre for advice. The Fair Work Ombudsman can investigate serious breaches of employment law and potentially take the employer to court. If they think what happened is covered by criminal law, they refer the case to the police. You can also go to a small claims court on your own or with help from your union.

What does an employment lawyer do?

Lawyers who are experts in employment law may work for unions, human resources departments or the government. They may help draw up employment contracts, check that employment contracts are consistent with Australian law, and give advice to employers and employees when there is a dispute.

Family law

Family law deals with the legal aspects of personal relationships, like marriage, divorce and custody of children. Australian family law is mostly federal, has a focus on the rights of children and encourages resolving issues outside of court. However, family law issues sometimes overlap with child welfare issues, and child protection laws are made at the state and territory level.

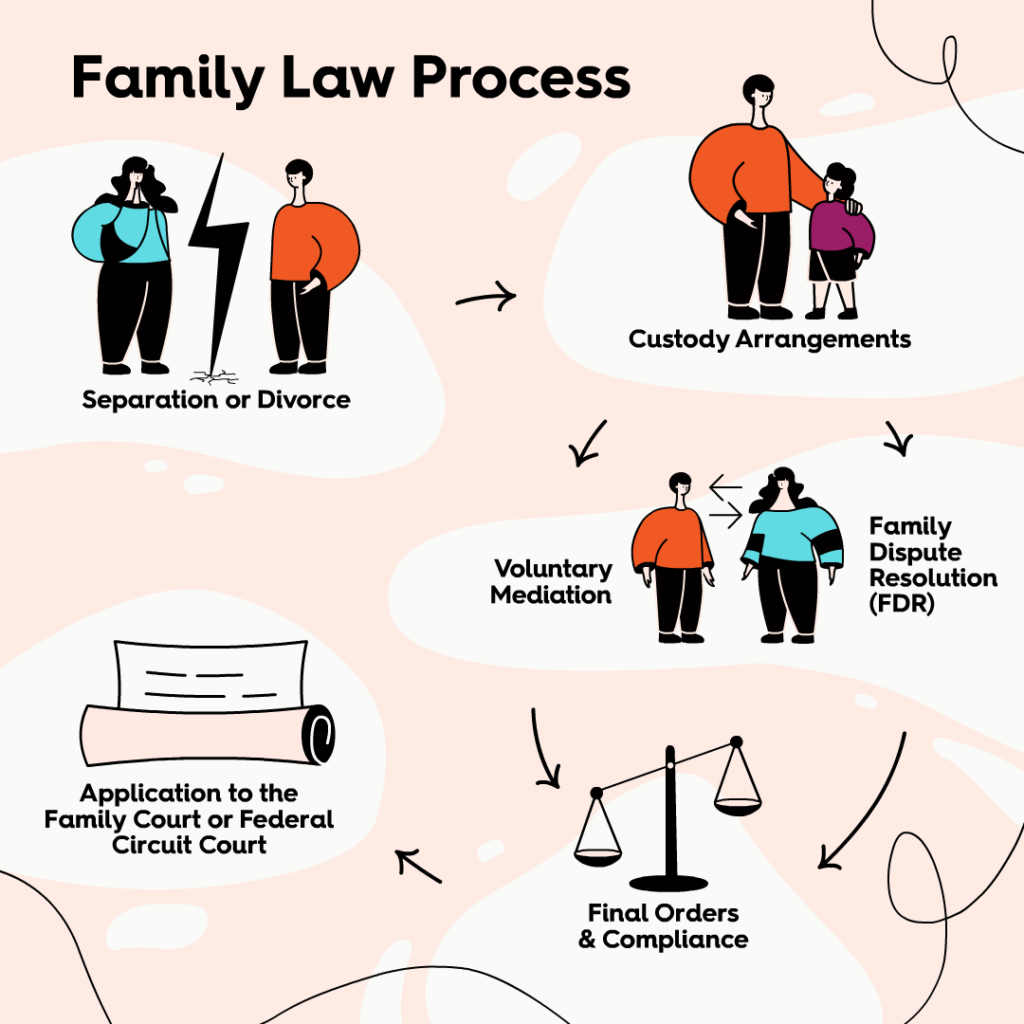

To understand how family law issues like divorce and child custody occur in the Australian legal system, see the flowchart below which outlines the typical process in Australian family law, from separation through to final court orders.

- Separation or divorce: In Australia, parties must be separated for at least 12 months before applying for a divorce. Couples may begin to address issues like property division and child arrangements during separation.

- Custody arrangements: Parents can agree on child custody arrangements on their own, or they may need help.

- Voluntary mediation: An independent mediator can help parents negotiate an agreement if they are willing to work together. If there is conflict, they may need formal family dispute resolution (FDR). FDR is a mandatory step in most cases before filing for parenting orders in court, unless there is a history of family violence or other exceptional circumstances.

- Application to the Family Court or Federal Circuit Court: If mediation or FDR fails, the next step is to make an application to the court. The court has the power to issue parenting orders, property orders, and divorce orders.

- Final orders and compliance: Once the court has issued an order, one party may appeal to have it changed. If someone isn’t following an order, the other person needs to formally tell the court about it for them to take action.

As you can see, this is a long and complicated process for many families – especially families with young children, who already have quite a lot on their plate. That’s why we believe families and children need holistic services that are well equipped for early intervention when legal needs crop up.

What does a family lawyer do?

Most family lawyers in Australia work for law firms and are hired by people with difficult or complicated divorce cases. Many family law experts work for the government, either in court or at a service that gives advice to parents.

Housing law

Laws around housing mostly come under either property law or tenancy law, depending on who owns the house.

Property law applies when anyone buys or sells land or housing, and includes rules about mortgages.

Tenancy law applies whenever someone rents housing from someone else. It sets out what rights and responsibilities tenants and landlords have in different situations, including social housing, but doesn’t cover short-term rentals or hotels.

Property and tenancy law in Australia is made at the state and territory level. If you need advice about your rights as a renter in your area, you can contact your local tenants’ union.

What does a property lawyer do?

Property lawyers in Australia often work for banks, corporate landlords or large corporations that own the land and buildings they do business in. They write and review legal documents when property is bought and sold, provide advice and go to court when there is a dispute.

Civil litigation

Civil litigation is what happens when two individuals have a legal dispute. The police are not typically involved and there are no criminal charges.

Civil litigation might happen when:

- Someone has been injured and they want the Court to rule that a person or organisation was responsible and should pay them compensation

- Two or more people disagree about the meaning of a will, or

- Someone owes someone else money and refuses to pay.

Corporate law

Corporate law is the law relating to how corporations are formed, what they can do and how people run them. It covers everything from starting a company to handling its finances and ensuring it follows the right regulations. For example, corporate law includes laws around mergers (when two companies combine), company structure (like whether the company is a sole trader or a corporation), and the responsibilities of company directors.

It also deals with what happens if a business breaks the law – whether that’s violating environmental regulations, failing to pay taxes, or committing fraud. Corporate law aims to makes sure that businesses operate fairly and transparently. In short, it helps maintain order in the business world by setting clear guidelines on how businesses should act, both towards their customers and other businesses.

Public law

Public law is the term for all kinds of laws involving the government, such as tax law, constitutional law and criminal law.

Criminal law

Everyone agrees that some private actions hurt the whole community. For example, violence doesn’t just affect the person who was injured – the health system has to treat victims of violence, and people behave differently if they’re afraid something harmful might happen around them. Criminal law is meant to cover the things that people shouldn’t do for everyone’s sake, like violence or theft.

The federal Criminal Code Act 1995 says what acts count as crimes throughout all of Australia. Each state or territory also has its own criminal laws for things the federal law doesn’t cover. The consensus on what should count as a crime can change over time, and many offences have been added to and removed from Australian criminal law throughout our history. For example, littering has only been a crime for about 50 years in some States, and homosexuality was still criminalised in Tasmania until 1997.

The police and courts enforce criminal law by punishing those who break it, with penalties ranging from fines to imprisonment. Some of the reasons for this are:

- To make the offender feel like it wasn’t worth committing the crime, so they don’t do it again (this is called specific deterrence).

- To make other people decide not to commit the crime because they don’t want to risk the punishment (this is called general deterrence).

- To protect the community by keeping the offender away from people they might hurt.

- To publicly acknowledge the harm done to the victim of the crime and to the community.

People under the age of 18 who are accused of breaking the law go through the juvenile or youth justice system, which is different in each state – for example, here’s the Victorian system. Sentences are usually different from adults, and many young people who are convicted are supervised in the community instead of being sent to prison. However, there is an ongoing debate about whether the juvenile justice system in Australia is fit for purpose, and the youngest age at which a child should be held criminally responsible and put through this system.

What does a criminal lawyer do in Australia?

Lawyers play two important roles in the criminal law process: prosecution and defence. In court, lawyers for the prosecution explain the evidence that suggests a particular person committed a crime. Defence lawyers make sure that the person who has been accused can understand what’s going on and present any evidence that suggests they didn’t do it, or that there are other reasons not to sentence them to the full punishment. Having legal representation can help to make sure that a trial is fair. If an accused person cannot pay for a lawyer, they can access one through legal assistance programs (see below).

Administrative law

Administrative law is all about what the government can and can’t do, how it makes decisions, and what you can do if you have a problem with something the government has done, which is often called an administrative action. If the government’s decision is related to something written in the Australian Constitution, the type of law that covers that is called constitutional law. The government doesn’t just include politicians. It also includes federal and state or territory government departments (such as the federal Department of Defence, or the federal or state Department of Health), officeholders and government bodies that are brought into existence by law, and the people who work in these organisations.

Whenever you interact with the government, for example applying for a Centrelink payment or the NDIS, there are administrative laws about how things should go. Decisions made by government have to made fairly, and they must provide reasons to explain why a decision was made. If you believe the government hasn’t followed these laws, you can go to a court or tribunal and ask them to look into it – more on that below. If the judge decides the government didn’t follow the law, they can undo the government’s decision and tell them to try again. Find out more from the Attorney General’s website.

What do administrative lawyers do?

Many experts in administrative law work for the government in different departments, making sure those departments are acting in the way the law says they should. Others work for courts and for organisations that work to hold the government accountable and challenge potentially unlawful decisions.

What is a legal issue or legal need?

Now that we’ve covered the different types of law, let’s move on to understanding ‘legal issues’ and ‘legal need’.

A legal issue is a problem that has something to do with the law – a problem that a lawyer might be able to help with. For example, if you’re told you owe Centrelink a debt for overpayments you never got.

We also call this legal need, especially when we’re talking about issues that affect whole communities or groups of people. When we want to find out which legal issues a particular group of people are dealing with, we do a legal needs survey.

For more detail, check out this page from the Law and Justice Foundation of NSW.

How to resolve legal issues in Australia

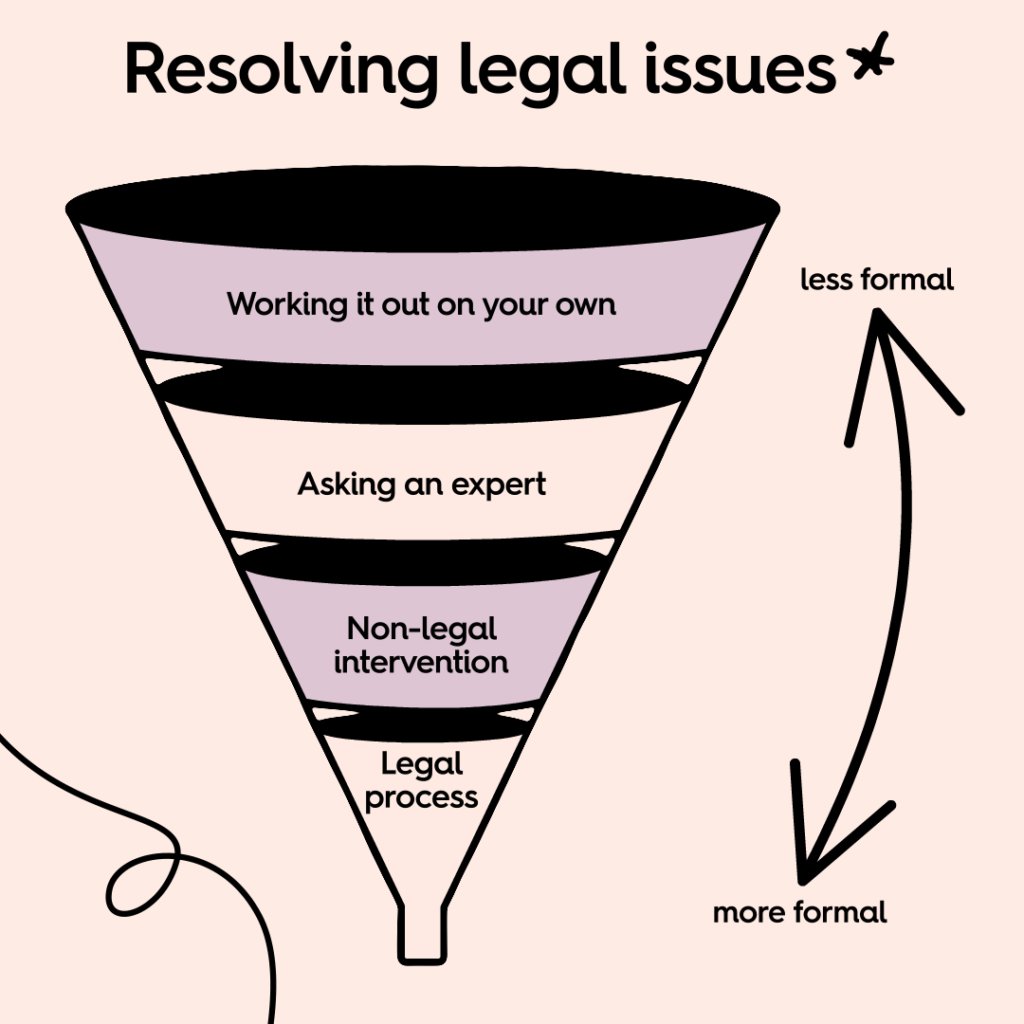

There are many ways to resolve a legal issue. Some are more formal and others are less formal. Most people start at the informal end of the spectrum, escalating to more formal methods if less formal ones don’t fix the problem.

In order from least formal to most formal:

Informal resolutions

Working it out on your own can be effective when the problem is simple and you know your rights. Many people find they can resolve the issue by speaking with the ‘other side’ of a dispute directly, perhaps after getting advice from friends and supportive professionals like doctors or teachers. When dealing with other parties involved in a dispute, it’s helpful to confirm discussions or decisions each of you has made in writing in case you need to refer to it later.

Asking an expert

If you don’t know what your rights are or how to proceed, you can talk to someone who does. This is where you might call information and advice services, legal assistance services, tenancy services, or unions. If your problem is related to the conduct of a colleague, teacher or support worker, you may try going through an internal complaints process that brings the issue to the attention of someone with authority over them.

Non-legal intervention

If talking to someone informally or complaining internally hasn’t had results, there are a number of more formal processes available that still don’t need to involve a lawyer.

These include:

- Alternative dispute resolution or mediation, which usually involves paying a fee to the mediator – this is a good option when both sides of a dispute want to work together to resolve it.

- Ombudsman’s offices provide free help when you have dispute with an industry body or government agency – there is a national ombudsman and one in each state and territory, as well as several for specific areas, like the Fair Work Ombudsman, which gives advice about employment disputes. Ombudsmen are not a one-stop shop, and they can only consider matters over which they have jurisdiction. Before you make a complaint to an Ombudsman, check their website to see if they deal with issues similar to what you are experiencing.

- other external complaints bodies, such as the Australian Financial Complaints Authority or the Human Rights Commission.

You can find a list of ombudsman’s offices and other complaints bodies at the Commonwealth Ombudsman website.

Understanding courts and tribunals

Criminal matters, and civil disputes that can’t be resolved less formally, usually come before a court or tribunal. Australian courts and tribunals also start with less formal processes and get more formal if the issue hasn’t been resolved. Many legal issues go to the ‘lower courts’ – tribunals and magistrates courts – in which you don’t need to be represented by a lawyer, although you can still choose to get legal advice beforehand. There are different state, territory and federal tribunals and magistrates courts, and the levels of each court might be called different names in different states.

Tribunals are usually run by panels of experts in specific legal areas. A tribunal is like a less formal, faster, less expensive court. Some tribunals were created to deal with very specific issues, like the federal Copyright Tribunal or the NSW Dust Diseases Tribunal. Others are quite broad, like the Administrative Review Tribunal, which covers all sorts of appeals against government decisions.

Magistrates are similar to judges. A magistrates court deals with civil cases (unless a large amount of money is in dispute) and is usually the first place a criminal charge goes – the magistrate can make a decision about minor cases or send the case up to a higher court. Magistrates courts have no jury, so the magistrate is the only one responsible for these decisions.

Cases that can’t be resolved in a magistrates court are sent up to the appropriate state, territory or federal courts, which either make a decision or send the case up to the High Court of Australia. These higher courts sometimes involve juries and you generally need a lawyer to navigate them. A jury is a group of ordinary people who are chosen to decide the ‘verdict’ of a case – whether a person is guilty or not guilty of a certain charge. Lawyers are not allowed to be a member of a jury.

What kinds of legal help can I get in Australia?

The first thing you might need when you have a legal issue is legal information, like what’s on this page – general information about the law, legal systems and processes, and what legal and other support services are available.

If you need more specific information about how the law applies to the problem you’re having and what you should do, that’s when you get legal advice. Lawyers are guided by strict ethical and legal rules and procedures. Someone who gives you legal advice has a legal obligation called a duty of care toward you, which is why general information helplines and websites often make sure to clearly tell you that they are not giving you legal advice (and neither are we!).

This may also trigger legal professional privilege, which means a court can’t make your lawyer tell them about the conversations you had with that lawyer while you were getting legal advice. Legal privilege exists so that people can be as honest as possible with their lawyers.

Once you’ve received legal advice, you may be able to resolve your legal issue by yourself. If not, a lawyer can either agree to represent you in an ongoing capacity, or do specific legal tasks for you as a once-off, like:

- preparing (or helping you prepare) a legal document like a statutory declaration, or

- writing a letter to someone else asking them to do something or stop doing something.

A lawyer can also refer you to another person or organisation that can help you with your specific issue. Sometimes they can do a secondary consultation, which is when permission is given for a practitioner to seek advice or share information with another practitioner – for example, when your doctor and your lawyer talk to each other about your problem.

If your legal issue winds up in a court or tribunal and you don’t have ongoing representation from a lawyer, many courts will assign you one, called a duty lawyer, to give you advice and potentially talk to the court for you.

What responsibilities does a lawyer have to their client?

If you hire a lawyer to help you, they must:

- put your interests first, including by giving you honest advice and not letting their own or others’ interests get in the way

- follow your legal instructions, unless there’s a good reason not to

- do their job properly and promptly, including by working carefully and without unnecessary delays

- explain things clearly to you so you can understand your legal options and make informed decisions

- tell you the costs of their work, and update you if that changes

- keep your information private unless you agree they can share it or the law requires them to share it, and

- avoid conflicts of interest – a lawyer must not work for you if it could create a conflict with someone else they represent or with other duties (e.g. their duty to the court).

What responsibilities does a lawyer have to the court?

Lawyers have to balance their responsibilities to you against their duty to serve the court. A lawyer’s main duty is to the court and the justice system. So if helping you goes against what’s right for the court, they must choose the court. They also have to treat everyone involved in the case—like court staff, the other side, other lawyers, and witnesses—with respect.

This means that when a lawyer is working to represent you:

- your lawyer can’t say things in court just because you ask them to

- they’re not allowed to lie or mislead the court, even if you tell them to

- if your lawyer finds out you lied to the court, they must ask you to let them tell the truth. If you say no, they have to stop working for you, and

- if you admit to your lawyer that you committed a crime, they can’t say someone else did it.

How do I access legal help in Australia?

For anyone facing a legal issue, knowing where to turn for help can be overwhelming. In Australia, there are several ways to access legal assistance, depending on the situation and whether the need is for private or public legal services.

Private legal assistance

Private legal assistance involves hiring a lawyer and paying for their services directly.

This option is usually the best choice for more complex legal issues, such as corporate law matters, personal injury claims, or disputes between individuals. However, you can engage a lawyer privately for any matter if you can afford it.

Some private legal firms have pro bono schemes which allow eligible low-income applicants to access their services for free or reduced fees.

Public legal assistance

Public legal assistance is typically government-funded or provided by not-for-profit organisations, making it a more affordable option for those who qualify. In Australia, legal aid commissions in each state and territory offer free or subsidised legal advice and representation, often focusing on criminal law, family law, and civil matters involving vulnerable individuals. Community legal centres (CLCs) also provide free legal advice, often specialising in specific areas like tenancy, domestic violence, or discrimination.

To access these services, eligibility criteria may be based on income, assets, or the nature of your legal problem.

How to access legal assistance

In Australia, legal assistance is available at legal aid commissions, community legal centres or law firms. By understanding the options, you can find the right legal help to address your needs and ensure you’re properly represented in legal matters.

Legal aid commissions

There is a legal aid statutory body in each state and territory, paid for by a mix of state and federal funding. Lawyers working for these commissions may run advice clinics, act as duty lawyers for people in court without their own lawyer, or do casework for people who are eligible. A legal aid commission can also pass on funding to community legal centres (see below), or grant funding to eligible people so they can pay another lawyer.

Whether you are eligible for legal aid depends on what type of legal problem you have and whether you can afford to pay for legal help yourself. Each legal aid commission has its own policy for making these decisions – they tend to be similar to each other, but you should always check the rules in your area.

The directors of the eight legal aid commissions combine at a national level to form the peak body National Legal Aid, which does national advocacy and research.

Community legal centres (CLCs)

There are 160+ community legal services around Australia. These are community based, independent non-profit organisations with an activist history. A CLC provides legal assistance to people living in a defined geographic area with civil and family law problems, including fines, credit and debt, parenting orders, family violence and child protection, and victim support. CLC lawyers often only do a small amount of ongoing casework – their main role is providing information, education and advice, as well as performing minor legal tasks. Some CLCs run specialist programs focused on a particular legal issue or demographic, such as welfare rights or women’s legal services.

You can find more information from the CLC peak bodies:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled not-for-profit organisations provide culturally competent legal assistance services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with criminal, family and civil law issues. They also do community legal education, prisoner through-care, and law reform and advocacy work.

Their peak body is the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service.

Each state and territory has an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal service:

- North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency

- Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia

- Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement, South Australia

- Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service (Qld) Ltd

- Aboriginal Legal Service (NSW/ACT) Limited

- Tasmanian Aboriginal Legal Service

Family violence prevention legal services (FVPLS)

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled organisations provide ‘wrap around’ holistic support to victims and survivors of violence, with specialised and culturally safe representation and support. Nationally, 95% of clients are First Nations women and children.

FVPLS provide legal help as well as other kinds of support. Their work includes:

- Prevention and early intervention

- Legal advice, case management support and service advocacy

- Child protection advice and intervention

- Recovery and healing programs, and

- Kinship liaison

For more information, see the peak body, First Nations Advocates Against Family Violence.

What is access to justice?

Australia’s laws are meant to apply to everyone equally, but not everyone understands the law or their rights – which means some people are at a disadvantage when it comes to standing up for themselves and holding more powerful bodies like an employer or the government accountable.

Access to justice is all about trying to balance out that disadvantage by making sure people can get legal help when they need it.

These are the main components of access to justice:

- Legal information – Is it available in plain language where everyone can find it?

- Legal capability – Can you understand when you have a legal problem and what to do about it?

- Legal help and legal advice – Is it available and accessible to everyone?

- Participation in legal processes – Can everyone get to where they need to be and understand what’s going on?

- Understanding a legal outcome – What does the judge’s decision mean for you? What can you do if you’re not happy with it?

Community legal education and public legal assistance are two important ways to increase access to justice. But what about the people who slip through the cracks?

What is health justice partnership?

One in five of the most disadvantaged people in Australia have legal problems they don’t address, often because they don’t recognise the issue as a legal problem, are too stressed, don’t have the time, fear damaging relationships, or have bigger problems to deal with. When these individuals do seek help, they are more likely to turn to a health professional rather than a lawyer.

Here’s where health justice partnership can be an effective solution. Health justice partnership bridges the gap by bringing together lawyers and healthcare professionals to provide legal assistance right where it’s needed most. For example, if a doctor discovers that a patient’s worsening respiratory issues are linked to mould in their rental property that the landlord isn’t addressing, the doctor can connect the patient with a lawyer. The lawyer can then write formal letters and take steps to prompt the landlord to act.

Health justice partnerships are designed to support people who are not well served by traditional service systems. These individuals often face complex, interconnected issues that don’t fit neatly into separate categories for health, legal, or other support services. People in these situations are particularly vulnerable to poor health and unmet legal needs, including those experiencing domestic and family violence, mental illness, elder abuse, poverty, or other forms of disadvantage. This approach is especially valuable for people who are also part of marginalised groups, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, or those from culturally and linguistically diverse communities.

Changing the system for everyone

Knowing more about how the Australian legal system works helps you understand your rights and your options when you find yourself in a difficult situation. But legal information is only the first step in ensuring access to justice for the people who need it most. That’s why Health Justice Australia works to support health justice partnerships that bring legal help to people with complex needs, lead research to discover the most effective ways of working in partnership, and advocate for policy and funding decisions to create lasting systems change.

The Email Newsletter

Subscribe to our quarterly email newsletter and stay up to date with what’s happening at Health Justice Australia.